Leaps and Steps: A Framework for Thinking About COP28 & Global Climate Negotiations

For the past two weeks, negotiators from 198 countries and over 70,000 people have gathered in Dubai for COP28. I've spent much of this time trying to make sense of what it all means.

For the past two weeks, negotiators from 198 countries have been meeting in Dubai at the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28) to update the United Nationals Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which entered into force in 1994. COP28 wraps up in Dubai today (December 12th).

I’ve spent the past two weeks trying to write something about COP28 that contextualizes what’s happened in a way that speaks to both seasoned climate policy followers and people who are new to the space. To accomplish these goals, I begin this piece with a brief overview of the UNFCCC, emphasizing its accomplishments while pointing out its limitations. Next, I highlight a few COP28 outcomes that give me hope. It’s a long piece, but I hope that you take the time to read it — and give me feedback on how to make subsequent technical pieces better. With that, let’s get to it.

What’s the Purpose of the UNFCCC?

The goal of the UNFCCC is the stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system…such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened, and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner."1 The five strategies for meeting this goal are: 1) expecting industrialized countries to do the most to cut emissions at home; 2) funding climate change activities in developing countries; 3) tracking progress through annual national greenhouse gas inventory disclosures; 4) structuring ways for developing countries to both grow their economies and limit emissions; and 5) formally considering and providing assistance for climate adaptation in the most vulnerable countries.

Updates to the UNFCCC are negotiated at the COP each year. While the framework strategies are sound, our ability to act on them as a global community is hampered by the fact that UNFCCC require consensus from all 198 countries that are party to the convention to reach agreements. That’s a lot divergent interests to wrangle; it’s a miracle that anything gets done. And yet, something big happened at COP21 in Paris.

A Leap: The Paris Agreement Changed Everything

The 2015 Paris Agreement established a legally binding goal to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” These global carbon goals have cascaded to regulators, NGOs, and companies. The Paris Agreement also provides a mechanism for countries to set and report on their decarbonization goals. While the COP28 negotiations focus on the latter, I’d like to take a moment to talk about the former.

Put simply, the Paris Agreement has influenced my entire career in sustainability since 2015. For businesses, it’s clarified the top-line goal: limiting the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This objective is present in corporate decarbonization frameworks such as the Science-Based Targets Initiative and The Climate Pledge, which was co-founded by Amazon in 2019 while I was a member of the sustainability team there (feel free to ask me about it). At a regulatory level, the 1.5°C target was adopted by what I view to be the leading global sustainability regulation, the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)

From a reporting perspective, countries began submitting their national climate action plans under the Paris Agreement in 2020. The Agreement operates on five-year cycles, with the ambition ratcheting up each cycle. At COP28, countries are sharing progress on their 2020 goals and starting to set their goals for the 2025-2030 cycle.

The Paris Agreement Update from COP28

Are we on track to meet the Paris Agreement? No, but we are making progress. When the Paris Agreement was signed, emissions were projected to increase 16% from 2015 to 2030; today, this growth rate has been revised down to is 3% (a 13% reduction!). This is progress, but we need to transition from slower emissions growth to actual reductions. To reach the 2°C warming pathway, we need to decrease 2030 emissions by 28% vs. 2015; to hit the 1.5°C pathway, emissions need to decrease by 42%.2 In other words, we’ve covered one-third to one-quarter of the ground we need to cover by 2030. It’s better than nothing, but not close to enough.

COP28 is an opportunity to bridge this emissions gap. It’s the culmination of the first-ever global stocktake, which was conducted to assess progress under the first Paris Agreement five year cycle. It has three parts: 1) gathering data; 2) analyzing the data; and 3) responding to the data with new plans. COP28 focuses on #3, or setting new targets. Based on the negotiations at COP28, countries will set new nationally determined contributions that they’ll bring to the next five-year planning session at COP30 in Brazil in 2030.

Will There be more Leaps Forward like Paris?

We need to do more and move faster to decarbonize. Yet global, consensus-based negotiations move slowly—especially when the topic impacts literally every person and being on Earth. I don’t see anything massive coming out of COP28, and a return of Trump to the Whitehouse in 2025 would put UNFCCC negotiations into a coma for the foreseeable future.

Looking on the bright side, maybe we don’t need more massive leaps forward. It’s possible that the Paris Agreement created all of the global momentum we need for the private sector and national governments to decarbonize. As someone who still feels the positive ripple effects from the Paris Agreement at work everyday, I remain tepidly optimistic that, while unlikely, this outcome is at least possible — and COP28 strengthened this belief.

Three Little Steps of Progress in Dubai

Though COP28 won’t deliver a leap forward like Paris, it’s provided several tiny steps forward. Let’s start with the COP itself: of the more than 70,000 people who attended COP28, only a tiny fraction took part in the formal climate negotiations; the vast-majority were in the Green Zone, which included 10 Themed Hubs, 600+ events, and 200 private company and civil society group exhibits. Just think of all of the conversations, connections, and agreements that will come out of the Green Zone.

The COP has joined Earth Day as a forum for companies, NGOs, and governments to announce new initiatives, establish partnerships, and float proposals. While there can be greenwashing, most of these steps forward are backed by good intentions. Sometimes, several steps can aggregate into a leap; other times, a step can grow into a leap on its own.

Let’s turn our attention to three signs of progress from COP28.

1. Funding Is Coming to Least Developed Nations, Albeit Slowly

The UNFCCC includes provisions that require industrialized countries to help less developed nations transition to low carbon economies and adapt to a changing climate. Here are two indications from COP28 that this is starting to happen.

Loss and Damage Fund - After 30 years of negotiations and advocacy by developing nations, a Loss and Damage Fund to help vulnerable countries respond to climate disaster was finally created. The funding pledges (>$700 Million, with a paltry $17 million from the US) are 1-2% of the expected annual amount required to respond to these disasters ($280 billion to $580 billion).3

There are a few ways to look at this. Most obviously, the massive gap between the funding pledged — not all of which will actualize — and the capital needed must be closed. Insufficient though the funding is, this fund marks the first time that developed countries have agreed to compensate developing countries for climate-related weather disasters. Precedent matters. It’s often easier to evolve a fund or institution than it is to create a new one. While there is a ton of work to be done, I view the creation of this fund positively.

Green Climate Fund - established under the UNFCCC in 2010, the Green Climate Fund allocates capital to low-emission and climate-resilient projects and programs selected by the developing countries implementing the work. At COP28, the Green Climate Fund received additional pledges that total $12.8 billion from 31 countries. Again, this is hardly a rounding error on the $2 trillion in annual capital needed by 2030 to transition to net-zero emissions by 2050, but it’s something. While global institutions need to show the way, I expect the majority of the capital needed to decarbonize to flow from the private sector, not global climate negotiations.

Institutions are being created and money is flowing—it’s progress, but not enough.

2. Real Progress on Methane, with Echos of the Montreal Protocol

When it comes to methane emissions, I’d like you to hold two ideas in your head: 1) we need to phase out fossil fuels ASAP; and 2) while fossil fuels remain part of our energy mix, we need to eliminate “wasted” emissions.

The UNFCCC is often compared to the Montreal Protocol on Substances the Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987), which is rightly viewed as the most successful global environmental treaty. Overall, I think that this is a facile comparison (a deep dive into why will require another post). In short, the Montreal Protocol focuses on eliminating and replacing a few ozone depleting substances made by a handful of companies with known replacements that are critical to refrigeration, air-conditioning and foam applications, whereas the UNFCCC focuses on greenhouse gas emissions that power almost all human activities. However, what’s happening with methane today reminds me of the success of the Montreal Protocol.

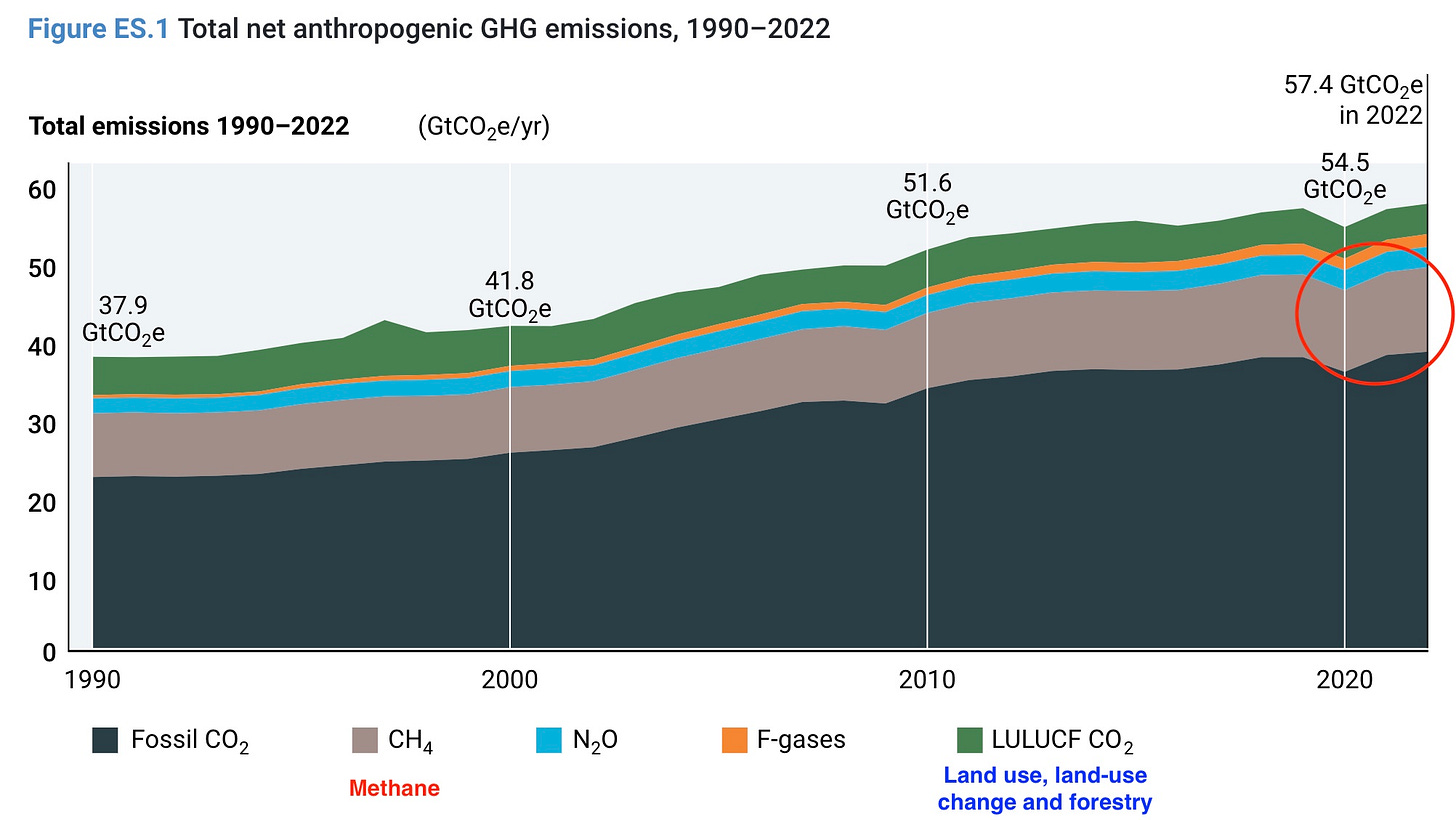

That’s great news, because we need to reduce methane emissions to meet global climate targets, period. Methane has more than 80 times the global warming power of carbon dioxide in the first twenty years after it’s emitted. It accounts for somewhere from one-third to more than half of human-caused warming despite being a quarter of all emissions. According to the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), halving methane emissions by 2030 could slow the rate of global warming by more than 25 percent.

This chart from the UNEP Emissions Gap report on human-caused greenhouse gas emissions since 1990 brings the point into focus (see methane in the brown area).

At the start of COP28, the world’s biggest state-owned and private oil companies, which represent half of global production, pledged to reduce their methane emissions by more than 80% by 2030. This comes shortly after an agreement by the US and China to work towards curbing methane, new EPA rules designed to limit domestic methane emissions in the US by eighty percent, and two years after the Global Methane Pledge was launched at COP26.

EDF President Fred Krupp highlighted the potential implications of this pledge when he said, “If those promises are met, it’s got the potential to cut temperatures we would otherwise see within the next decade … more than anything agreed to at prior COPs, more than anything I’ve seen in my entire career over 30 years.” To paraphrase Joe Biden, that’d be a BFD.

The key parts of the plan include: the elimination of flaring natural gas at new oil wells, better monitoring for methane leaks at well sites and compressor stations, equipment standards that reduce the emissions from controllers and storage tanks, the deployment of remote sensing technology to detect massive methane leaks, and international monitoring and funding to help companies in poorer countries locate and address methane leaks. Taken together, these measures could reduce the amount of methane that is leaked directly into the atmosphere from 2-3% to near zero (0.2%).

3. A Phase Out of Fossil Fuels is on the Table

In the lead up to COP28, France and the US proposed a plan to halt the private financing of coal-based power plants. Coal-fired power plants have long lives; the average age of a coal-fired power plant operating in the US is 45, though many are slated to be retired after 50 years of use. This means that coal-fired power plants financed today may still be in operation in 2075 — or, to make me feel old and put it another way, well after the actuaries expect me to die.

Much like it’s harder to create a fund or pledge than it is to improve one, shutting down a power plant that’s producing energy is way harder than preventing the construction of a new one. This is why I’m a strong backer of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, which calls for a “concrete, binding plan to end the expansion of new coal, oil and gas projects and manage a global transition away from fossil fuels.” To date, it’s been endorsed by 12 countries, 97 sub-national governments, and more than 620,000 people (you can also endorse it here).

While neither proposal has a chance of being adopted at COP28, we need to stop building additional fossil fuel infrastructure. Proposals like these, especially if backed by the full power of the US and French governments or the moral standing of small island states that risk vanishing under a rising ocean, can make a real difference.

A third sign of progress is that negotiators are considering language to “phase out” fossil fuels — a noticeable step up from the COP26 language to “phase down” their use. As of December 8, the draft text of the COP28 agreement “Calls upon Parties to take further action in this critical decade towards" [one of the following five options]

Option 1: A phase out of fossil fuels in line with best available science;

Option 2: Phasing out of fossil fuels in line with best available science, the IPCC’s 1.5 pathways and the principles and provisions of the Paris Agreement;

Option 3: A phase-out of unabated fossil fuels recognizing the need for a peak in their consumption in this decade and underlining the importance for the energy sector to be predominantly free of fossil fuels well ahead of 2050;

Option 4: Phasing out unabated fossil fuels and to rapidly reducing their use so as to achieve net-zero CO2 in energy systems by or around mid-century;

Option 5: no text

I think that Option 2 is best, Options 1, 3, and 4 are various levels of ok-but-not-great, and Option 5 would be a disaster. Negotiations on this wording are likely to stretch to the last minute of the COP, so I’ll update this once the final language is known, but as of December 9th I’m guessing that Option 4 is the most likely outcome.

[December 13th update: The final text was better than I expected! It includes:

Further recognizes the need for deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in line with 1.5 °C pathways and calls on Parties to contribute to the following global efforts, in a nationally determined manner, taking into account the Paris Agreement and their different national circumstances, pathways and approaches. 9Two quick asides: 1) note the mention of Paris, and 2) I’m only going to copy a few key sections of the agreement below)

(b) Accelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power;

(d) Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science; (note how this combines several options above)

(h) Phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions, as soon as possible; (this is one the US should take seriously)

Phasing-down coal, transitioning away from fossil fuels, and phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies — there are all steps in the right direction. I’m very more cautiously optimistic about a breakthrough in Brazil in 2030 now.]

Conclusion

The UNFCCC provides a global floor for climate action. Countries, companies, and regional blocs can — and must — do more. Nonetheless, this baseline matters because it both sets a global minimum and shapes the global conversation around sustainability. When compared to the “debate” around climate in the US, which is centered on climate denialism, the Paris Agreement serves as a reasonable starting point for action and clear-eyed negotiations on what needs to happen next.

The Paris Agreement is a strong platform for additional steps forward. While the steps we saw at COP28 may seem small, each one pushes the conversation forward and makes the next leap (e.g. a non-proliferation treaty on fossil fuels) more and more attainable until a leap happens and it becomes reality.

Will the leaps be big enough and close enough together to limit warming to 1.5°C or 2°C? I don’t know. There are strong, vested interested that will fight to maintain the status quo—every attempt to strengthen emission standards or decommission fossil fuel infrastructure early will be meet with fierce resistance.

And yet, I remain cautiously optimistic. I have to be. The reason is simple: if we don’t believe that a better future is possible, then we’ve already lost. Doomerism has a perfect record of failure. While it’s important to be honest, it’s imperative not to become jaded and cynical. That kind of thinking bring you, and everyone you engage with, down.

What I do know is that if each of us does our part to take a small step forward, those steps can become a leap, and that leap can become the springboard to a better future.

If you found this post interesting, please share it with your network to help Bright Spots grows.

If someone forwarded this to you or you found the link on LinkedIn, please subscribe.

Thanks for reading. It means a lot to me.

JR

https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/what-is-the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change

https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/11/30/climate/cop28-loss-and-damage.html