How to Find Flow at Work

We spend too much time working, thinking about work, and talking about work for it to be a bore. We can improve our working lives by discovering which jobs help us flow.

I track important facts back to their original sources because paraphrasing loses nuance. Over the years I’ve built up a small library of books about finding your purpose and thriving at work. All of these books emphasize the importance of achieving flow, so it was only a matter of time until that I bought Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. It did not disappoint.

Csikszentmihalyi defines flow as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” When doing the activity becomes the reward, we’ve entered into a state of flow. Csikszentmihalyi defines these as autotelic activities, “derive[d] from two Greek words, auto meaning self, and telos meaning goal.” He contrasts these with exotelic activities that are completely driven by external reasons, like working solely for a paycheck.

A great and challenging thing about life is that we evolve, learn, and grow – tasks that were impossible last year can become routine and bring us great joy with enough patience and practice. I’ve personally witnessed this play out in my own household with two of the flow activities Csikszentmihalyi mentions in the book; yoga, which he categorizes as a physical practice, and reading, a mental practice.

After three years of lower back pain, my doctor told me that I didn’t need to accept a constant but tolerable level of pain forever. As part of my physical therapy regime, I had to build strength in my core and the right side of my tuchus while loosening up my hamstrings. Many of my physical therapy exercises reminded me of basic yoga poses. When I graduated from physical therapy I committed to a daily yoga practice.

I’d joined my wife for yoga classes on-and-off for the past decade, but never more often than once a week. I’d been dabbling with yoga for so long that I tried to start my daily practice with intermediate classes that I lacked the strength and flexibility to handle. My arms shook, my core burned, and I repeatedly collapsed into a heap on my mat. After a few days, I pivoted to a series of beginner classes that were more appropriate. While they had some challenging moments, these classes left me feeling refreshed and energized. After completing the beginner series, my flexibility and strength improved enough that I moved on to intermediate classes, where I’ve continued to push myself and improve over the past few months. While my levels of strength and flexibility are still basic compared to those of a devoted yoga practitioner, I’m light-years ahead of where I started.

I’ve seen the same type of methodical growth in my oldest son’s reading ability. Max went from crying and struggling to sound out basic words as a first grader to picking up Harry Potter books and reading for pleasure as a third grader. While two years seems like an eternity for kids and parent, it’s just a blip over the course of a lifetime.

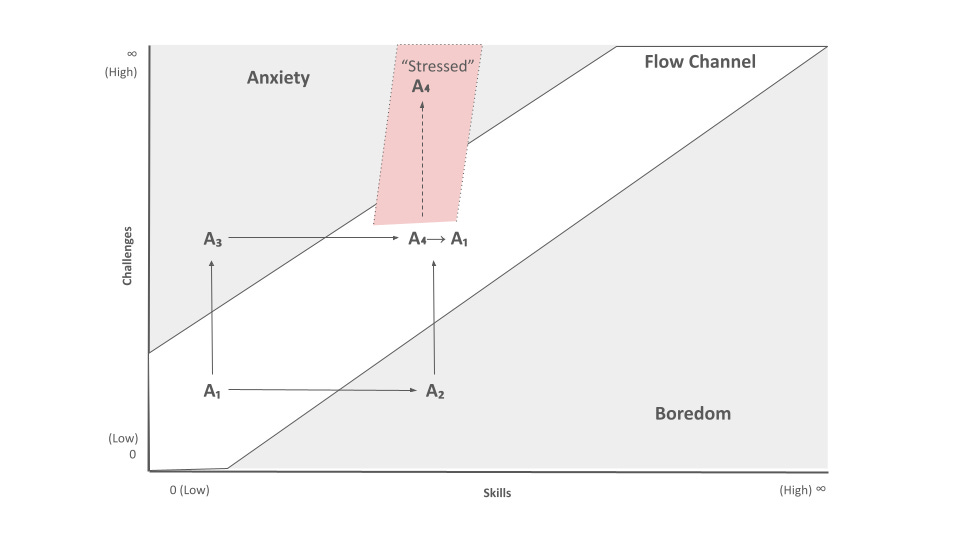

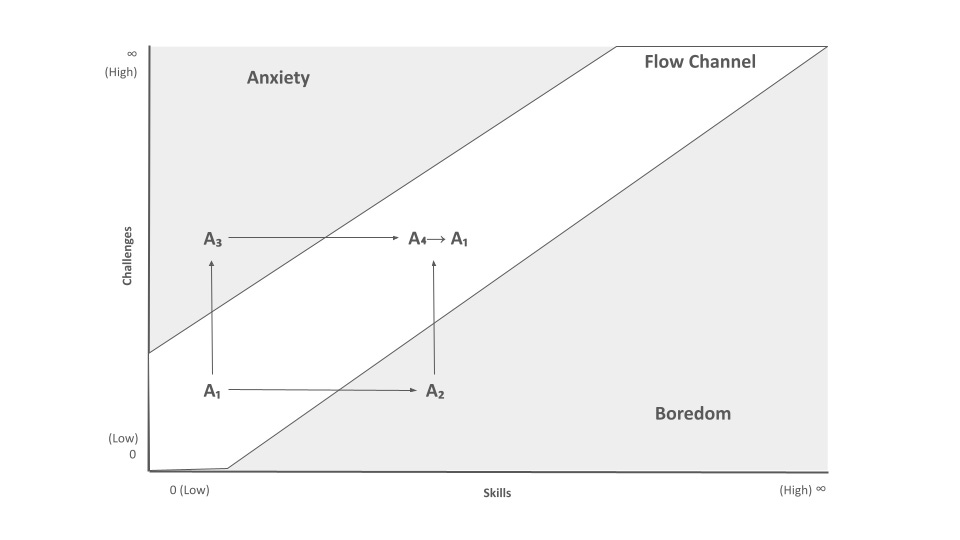

At the beginning, both Max and I were at (A1) in the helpful graphic that I’ve adapted from Flow above. As we practiced, we advanced – sometimes, we returned to a book or yoga pose and found that our skills had progressed to the point that it bored us (A2). Other times, we picked up new books and sequences that pushed us outside our comfort zone and into position A3. For me, the best feeling is when something that was beyond me becomes possible, like when I got into a crow pose and surprised myself by jumping back into chaturanga dandasana.

I can feel my body slowly adjusting to a new equilibrium. Poses that used to be a stretch (A4) have become my new baseline (A1). In the same way, the little boy who used to fight and try to memoize his way through the Dr. Maggie’s Phonics Readers that my Mom, a retired reading teacher, sent us and helped him practice over Zoom when it became too challenging for me to assist him, is now reading everything in sight. Both of us are getting more joy out of the activity as we progress up and to the right in the flow channel.

Finding Flow at Work

Adults spend much of their time working, thinking about work, or talking about work. What you do for work is how conversations between adults begin. Given the role work plays in our self conceptions, we should seek out autotelic jobs that enable us to flow.

One complication is that the challenge needs to increase as our skills progress to enable flow. Some jobs are better designed for flow than others. While they rarely sleep and in my experience tend to complain about their hours and lifestyle, every surgeon I know waxes poetic about how the hours and outside world melt away when they are immersed in a complex surgery. All that matters is the work. Surgeons spend a decade training and honing their skills, slowly increasing the challenges required of them as they move along the path from medical student to resident, fellow, attending, and maybe eventually chief surgeon.

One of the reasons that I keep writing this newsletter is that I can select more challenging topics and goals as my skill as a writer increases. When I started Bright Spots, my goal was to publish one to two articles a month; searching for topics was a constant source of low-level anxiety that stretched me to A3. As I got into the rhythm of writing, I moved to A4. To continue challenging myself, I decided to narrow and deepen the focus of my writing to topics related to purpose, professional growth, and sustainability that can coalesce into a book. For this piece in particular, I’m adapting a draft book chapter, which is a new challenge.

While the goal is to find something that keeps us in the flow channel as we move through our careers, this is easier said than done. When the challenge required and your skills are misaligned, a role can sour, leading you to languish or become stressed.

Languishing

When my skills outpace the challenge at work, I get bored and begin to languish. My first job out of graduate school was an inside sales role at a company that specialized in ecommerce warehouse logistics for apparel brands. The role had what I thought I wanted: it operated in the physical world, had an innovative business model backed by novel technology (they used robots to handle many of the tasks inside the warehouse), and gave me a chance to develop new skills.

I learned concrete business skills – how to manage a sales pipeline, nurture prospects, negotiate on price, close deals, etc. – that are quite useful. But after a few months, the reality of the day-to-day started to wear me down. I read fashion magazines to identify brand targets, trawled LinkedIn looking for contacts to cold email, guessed at the pattern used for email addresses at each company before sending those emails out, , sent follow ups notes to the email addresses that didn’t bounce into the abyss, and eventually had a few phone calls with prospects. Some of these phone calls led to proposals, sales, and new customers. The more of these calls I had, the better I got at the work, but the challenge increase in the right way for me. I didn’t feel a rush when engaging a new prospect or closing a deal. Instead, I found myself thinking about ways to improve our overall sales and marketing strategy. I ended up tweeting as a robot and launching our inbound marketing strategy, but that work didn’t really speak to me, either. I spent early mornings and weekends poorly writing fiction and looking for a job that would stretch me, which is how I ended up at Amazon next.

Even at Amazon, I got twitchy after 18 months in any role. I now make it a point to switch or at least reimagine my role every 18-24 months. At the same time, I lean into hobbies that challenge different parts of my brain to counteract professional ennui. Beyond writing fiction during that sales job, these hobbies have included training for triathlons, attempting to start a rent-and-rotate toys business on the cusp of a global pandemic, getting involved in local politics, and this newsletter.

Stressed and Overwhelmed

The opposite of languishing is undue stress and overwhelm. This happens when the challenge outstrips your capabilities, and, no matter how hard you try, you can’t close the skill-to-challenge gap.

As I write this sentence, my wife Allie is at the pottery studio, indulging her hobby and passion for throwing pots. Over the past year, I’ve watched with a sense of awe and wonder as she has discovered a passion for pottery that neither of us knew about during the first 15 years we were together. We live close to a pottery studio and creating with her hands brings her joy, so she finally enrolled in a class. The change in her overall life satisfaction was both striking and immediate. Even though she struggled to center the clay for weeks, she returned home from each session after our normal bedtime more energized than before. Over time, her skills have improved in direct proportion to the challenges she sets for herself. She is flowing.

I tried pottery as a high school student and struggled throughout the entire semester. No matter how hard I tried and how much effort I put into it, I couldn’t center the clay or mold any of the designs that I’d imagined. It was so exasperating that I didn’t pick up clay again until Play Doh appeared in our house. Even when working in Play Doh, I limit myself to molds, snakes, and the occasional unidentifiable four legged creature.

I think in words, diagrams, and conceptual charts. Give me a blank piece of paper and I’ll happily get to work on a problem. Give me a blank spreadsheet and ask me to figure something out, and I’ll freeze. I know people who open up Excel when they want to work through a problem; I have literally no idea how they are able to do this. It just isn’t how my brain works.

Once long, long ago, I had a verbal job offer that was contingent upon my passing an Excel skills review. The review was painful, and the offer never came through. A few years later, history almost repeated when I went through the Excel section of the interview process at Amazon. Thankfully I did well enough, the offer came, and after arriving at Amazon I learned my way around a spreadsheet and began writing basic SQL queries. The work was right at my edge in a good way.

I left Amazon during the pandemic to take a sabbatical and focus on my kids. During naps and evenings, I wanted to challenge myself. Like many people in Seattle, I was surrounded by coders: software developers, data scientists, sustainability scientists. The developers I knew talked about how the hours would melt away as they became immersed in a problem. I was seeking flow and challenge, so I decided to try my hand at coding.

As someone who likes to start at the beginning, I enrolled in CS50, the foundational, exceptionally popular, and free Introduction to Computer Science at Harvard. I diligently watched the lectures, took notes, and started going through the course. I got through the first three weeks and then I hit the wall. I watched the lecture, tried to do the problem sets, went through all of the hints and tips available, and I just couldn’t figure it out. I thought about it all the time, my cortisol spiking as a result. I became more anxious and had a hard time focusing on my kids. I kept trying – and failing – to solve these problem set questions for a free, optional, online class I was taking. Eventually, I stopped trying to solve the problems and accepted that learning how to write algorithms in C wasn’t something that was going to come naturally, or within the course of the general study habits I’d acquired over a lifetime of schooling, for me. And that was ok. I learned that thinking at the level of sequential, logical specificity needed to write code wasn’t something I could acquire easily on my own.

Realizing that coding stressed me out was hard to accept. Over time I came to appreciate that the things I’m good at–thinking in conceptual diagrams and connections, writing ideas down, etc.–make me a great peer and partner for people who write code and think in a more linear manner. While I will never be a coder, by working with people with that complementary skill set, I get more done as a team than I could alone. I’ve also learned that I’m mostly likely to flow with others when I’m part of a multidisciplinary group working on a hard problem.

We only have one career. It’s important to keep trying, testing, and moving towards finding a career that allows you to experience flow. At the same time, tasks that enable you to flow are only part of the equation; the other is living a life of meaning with a deep sense of purpose.

I’ll have more to say on this in the future, but you can refer back to my piece of ikigai for some of my early thoughts on the topic.