Find Your Ikigai

Finding purpose and meaning is central to living a good life; the Japanese concept of ikigai can help each of us discover our purpose.

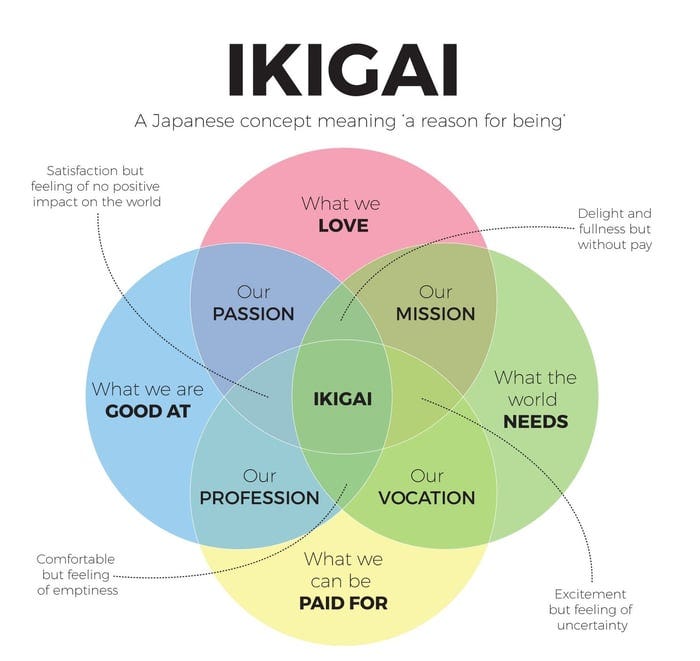

Your ikigai is what makes your life worth living. While it roughly translates to “the happiness of always being busy,” it connotes one’s raison d'être. Ikigai happens where what what we love, are good at, and can be paid for converge with what the world needs. While it’s easy to focus on one or two of these inputs and ignore the others, doing so can leave us unbalanced and unfulfilled. It’s challenging, but I believe ultimately more rewarding, to strive for achieving all four at the same time.

Imagine the ikigai image above as a set of interlocking circles, with you as a ball below. Your job is to balance all of these interlocking circles to keep them off of the ground. If you roll too far to one side, some of the circles will fall to the floor and you’ll be out of balance.

Think about where you are today. Are your ikigai circles all off the ground?

When I think about myself as such a ball, I see parts on the ground. I’ve built my career based on what I think the world needs (for the last 15 years, this has been working to slow climate change). At an abstract level, the work is rewarding — I feel as though I’m making a difference — but on a personal level, it’s challenging. I’ve started from an edge of the diagram above and tried to work to the middle, instead of starting from a spot that’s closer to the middle, such as where what I’m good at and love to do overlap, and inching towards the center.

In an attempt to help center myself and each of you, I’m going to provide some thoughts on each component of ikigai, leaving what the world needs for last.

What we Love

Do what you love sounds so simple, yet it’s deceptively hard to achieve. For starters, it’s hard to know what we love. We aren’t born with a map, and the world is so vast that each of us has many latent passions that we may never uncover.

I believe that the best way to discover what we love is to try, experiment, and evolve. Over the past year, I’ve watched with a sense of awe and wonder as my wife has discovered a new passion: pottery. During the first 15 years I knew her, pottery was not something we talked about. Yet we live close to a pottery studio and creating with her hands brings her joy, so she finally enrolled in a class earlier this year. Once she started throwing pots, the change in her overall life satisfaction was both striking and immediate. Even though she struggled to center the clay for weeks, at the end of each session in the pottery studio she returned home more energized than after even the best zoom call. Over time, her skills and outputs have improved—as has the number of bowls and mugs in our house—but her joy has remained and, if anything, expanded.

She isn’t going to quit her day job to become a ceramicist…yet. But maybe she will one day. What inspires me, and what I take from watching her, is that the first step to discovering our passion and ikigai is an openness to trying new things. Limiting what those new things are based on how you think others will perceive you, or what you believe the world needs from you, could prevent you from discovering your purpose.

What we are Good at

David Epstein recently published a great article on the difference between “fast risers” and “slow bakers.” The world is dynamic, as are we. It’s easy to conflate how good we are at a skill today with how good we can become at it—or to think that what comes easiest is what we’re best at. These heuristics are wrong.

The parable of the tortoise and the hare has stayed with us for millennia because it’s true. Epstein points out that some people who were long labeled as mediocre keep improving long after their “more talented” peers have topped out, burned out, or moved on. We see this with athletes who struggle to make it to the pros and then evolve into stars (Tom Brady was famously selected 199th in the NFL draft but went on to be the undisputed greatest player of all time). Another example is Adam Grant, who failed his initial writing exam at Harvard but went on to become a famous academic who moonlights as a best-selling author of highly accessible books. While very few us will go on to be the best in the world at something, if we stick to what comes easily, we risk limited what we can evolve into being.

So, what am I exploring these days? There’s a hint here, but a more explicit discussion of exactly what it is will have to wait for another piece that I’m slow baking in the background.

What we can be Paid For

Meet any stranger at a cocktail party—or in my case, the playground or a kid’s birthday party—and the conversation quickly turns to “what do you do (for work)”? In America, we define ourselves by what we get paid for. This doesn’t have to be the case. In Ikigai, the Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life, the authors interview residents in Ogimi, a town in Okinawa, Japan, that it home to the most centenarians on Earth. These people have deep community bonds, make time for friends, celebrate often, are active everyday (almost all of them are avid gardeners), try not to worry, rarely rush, don’t overeat, take pride in honing their skills, and are optimistic. They do not live to work; they age with grace and humor because they remain active and engaged. Their ikigai is in their busy, diversified, and rich lifestyle—not their work.

That said, there is no single path to fulfillment: some people who find their ikigai through work such as artists stay active in their chosen vocation until they die;other people use retirement as an opportunity to discover their ikigai. My point is that what we are, and what helps us live a long and worthwhile life, may not be what we’re getting paid for today. You may have great colleagues, but will they be your friends once you leave that company?

For some people, working for a paycheck gives them the financial security needed to explore their ikigai. Many authors, from J.K. Rawling to T.S. Elliot and Toni Morrison, wrote on the side until they published their first works. These authors were eventually paid for what they were good at and loved. The world needed their art, but that wasn’t clear until that art became public. By putting themselves out there, they were able to demonstrate that what they were good at and loved was something that the world needed as well.

What the World Needs

We live in trying times: the climate is warming and weirding; populism and authoritarianism are on the rise, including potentially at home; wars with existentially high stakes dominate the headlines; and technologies like AI threaten to further destabilize our already shaky society. None of these are easy fixes, and each could benefit from our grit, determination, and genius. Yet we only have so much time, and need to be selective about what we invest in.

I’m someone whose always chased the biggest challenge and sought meaning through my involvement, even if only in a small way, in the work (I think) the world needs. If I’m not in the room where it happened—and I’m surly not—at least I’m in the right zip code, wrestling with climate change, one of the most pressing issues of the day.

Or am I in the right zip code? My current framing may be a myopic way to think about what the world needs. Perhaps instead of trying to identify the most pressing issues and then working towards our passions and competencies, it would be better to start from our areas of strength and joy and then work towards what the world needs. This is a subtle shift, but I think that it could have big benefits for our mental health, balance, and the overall amount of good we’re able to do. The world needs so many things, and it’s hard to know where our greatest impacts will be. I have a friend who left a corporate job to volunteer at an elementary school, pursue his passion for crosswords and bouldering, and coach youth sports. It’s possible that his influence on those young athletes will shape their trajectories, and the world, more than his corporate sustainable work. To suggest otherwise is to claim a better understand of a complex world than I think any of us has.

Strive for Ikigai

It’s easy to find yourself in a “good enough” grove and stay there. There are so many ways to distract ourselves that it’s easy to forget that things can get better if we’re intentional and courageous. Yet I think that we should strive for ikigai. I’ll close with a quote from yung pueblo’s the way forward:

if you embrace growth, remain humble, and are not afraid of stepping outside of your comfort zone, you can be sure that your best work and the best parts of your life have not happened yet

Love this concept -- reminds me of our talk earlier this year on The Courage Effect! Incorporating this into my end-of-the-year reflections . . .