How to Escape the Shitthropocene of Food

In an era of homogenized and unhealthy food, eating slowly and with intention is a radical act.

[JR’s note: Publishing early and looking for feedback.]

A family is getting ready for dinner. I would say sitting down to dinner, but more often than not, dinner is an asynchronous affair–a child wanders into the kitchen to grab a plate before heading back to his room to game. A parent and a child are both seated at the table, but their attention isn’t on each other, it’s on their devices. They swipe and peck at their screens between bites of burger and sips from their sodas. Licking the orange cheetos dust from their fingers is the only thing that interrupts the scrolling.

The story of this meal began a little over a year ago, when a calf was born on a ranch. For the first six months, the calf lived a good life in a pasture: nibbling grass, drinking milk, playing, and lazing around. After being weaned, things went downhill–fast. First, the calf was separated from its mother, leaving its mom to bellow for days on end, looking for her calf, which had been moved to a backgrounding pen. In that pen it was introduced to corn, hay, and a toxic antibiotic that’s required for it to stomach this transition to a corn-based diet. After putting on 600 pounds over a few months, the cow is sent to a concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO.

At the CAFO it’s surrounded by tens or hundreds of thousands of other cows. It’s fed corn mixed with liquified protein and fat. The cows sleep in their own shit, which flows into a series of langons that leach out and contaminate the environment. People who visit smell the CAFO long before they see it. Our cow stays at the CAFO until it becomes obese enough to be trucked to the slaughter house. There it lines up, waiting to go through the blue door, where it will be killed with a metal bolt to the brain, after which it’ll be chained up, bled via a stab to the aorta, and then sent to have all of the shit cleaned off of, which is done to prevent bacteria like E. coli from contaminating the meat.1 Odds are that, after being butchered, our cow’s liver will be disposed of–too damaged from the corn and antibiotics to be for sale (this is why it’s hard to find beef liver). A few steps down the industrial food chain, part of that cow ends up as in patty form, where it’s bought at a grocery store.

The corn that went to feed our cow-turned-burger isn’t the kind we eat –that’d be sweetcorn, which makes up just one percent of corn harvested in this country–but field corn. Field corn, the 99 percent of corn, isn’t something we eat directly. Rather, it’s used to produce ethanol; animal feed, often for ruminants like cows that aren’t designed to eat it; corn starch, which is further processed into the enriched corn meal; and everyone’s favorite sweetener, high-fructose corn syrup. Some of the fertilizer required to grow our massive monoculture of field corn becomes nitrogen runoff that flows down the Mississippi until enters the Gulf of Mexico, where it produces a massive dead zone.

Some of the corn that didn’t go to feed the cow or power a car ended up in a at a Frito-Lay factory, where it’s pushed through an extruder at high enough heat to pop into that iconic cheeto shape, dipped in hot vegetable oil, and then sprinkle it with a “Cheese Seasoning” that contains whey, cheddar cheese, canola oil, maltodextrin (made from corn of course) and a whole lot of other shit. And just like that, your cheetos are ready to be packaged, shipped, and eaten.2 The salt and MSG that make cheetos so delicious make people want to keep eating them once they are full. This tendency to overeat is exacerbated for people using a smartphone.3

More corn can be found in the high fructose corn syrup that sweetened the sodas on the table.

Everything about this meal is shit–the ingredients; the lack of dignity afforded to the animal that was eaten; the amount of industrial processing that went into producing the corn, cheetos, and soda; the complete lack of connection to the seasons. True, cheap and plentiful food prevented the mass starvation many predicted in the 1970s, but the costs were high. Eating like this deprives the body and soul of what we need to live healthy, connection, and intentional lives. Food made this way turns us into the last stop on the food system conveyor belt of the shitthropocene. It doesn’t have to be this way. To live a full life, it can’t be this way.

The Slow Food Movement

The push back against the industrial food system accelerated in 1986, when plans to open a McDonald’s next to the Spanish Steps in Rome led to protests across Italy. These protests against the homogenization of food led to the founding of the Slow Food movement.

Published in 1989, the Slow Food Manifesto begins:

Born and nurtured under the sign of Industrialization, this century first invented the machine and then modelled its lifestyle after it. Speed became our shackles. We fell prey to the same virus: 'the fast life' that fractures our customs and assails us even in our own homes, forcing us to ingest ‘fast- food.’

The Slow Food movement believes that food–in particular, traditional, local cuisines–is the surest way to reclaim our cultural heritage and promote international exchange and understanding. It’s a reaction to our modern obsession with efficiency and speed that threatens our cities and environment. Its goal is to help us “to rediscover the rich varieties and aromas of local cuisines.”4 The manifesto concludes, “Slow Food assures us of a better quality lifestyle. With a snail purposely chosen as its patron and symbol, it is an idea and a way of life that needs much sure but steady support.”

The launch of the slow food movement coincided with the birth of foodie. A neologism first coined in the Official Foodie Handbook of 1985, foodies don’t just eat to meet their biological needs. Rather, food is a hobby and expression of self. What unites foodies and the slow food movement is a conviction that good food is a door to a richer life.

Food culture further ascended when No Reservations premiered in 2005. There wasn’t anything like it on tv–or anyone like Anthony Bourdain. Edgy, up for anything, and with the eye of a novelist, Bourdain transported us from our living rooms to a world filled with organ meat, exotic flavors, and friendships forged on the nonverbal communication made possible by good food and plentiful alcohol. He showed how sharing great food is what unites us as humans.

Today, Slow Food is an international movement with chapters in 160 countries, over one million activists, and more than two thousand local communities. These people are committed to “a world where everyone can enjoy food that is good for them, good for the people who grow it and good for the planet.” With thousands of projects going on at any time, the Slow Food movement defends biological and cultural diversity; educates, inspires, and mobilizes people; and advocates for better public and private sector policies.

Slow Food, foodies, and food-as-television gave rise to a generation of people like me who traveled to eat. This increasing demand, in turn, inspired a new generation of chefs and restaurants that became destinations.

Slow Food Fantasies

Like many, my pandemic reprieve from the blur of work, childcare, remote kindergarten, and anxiety was food porn. I was particularly taken with Chef’s Table, which featured great cinematography and insanely talented people like Magnus Nilsson, the chef at Fäviken, a destination restaurant in such a remote corner of Sweden that diners needed to spend the night. All the ingredients were local, of course, and combined hints of the traditional and avant garde. After finishing an episode, I went to the kitchen, hungry and deeply unsatisfied with the fried egg and cheerio options that awaited me. One day, I vowed to experience food porn for myself.

It was worth the wait. The opportunity finally arrived earlier this year, when my wife and I each celebrated milestone birthdays at Pluvio, in Ucluelet, British Columbia, Ucluelet is a truly magical town of 2,000 people. Located on the west coast of Vancouver Island, it’s just south of old growth rainforests, the most consistent surf break in Canada, and its more famous neighbor, Tofino. People come for the surf and nature; they stay for the community, the slower pace of life, and the food. Good god do they stay for food. Everything we ate, from breakfast sandwiches to smoothies, was prepared with care. But nothing came close to Pluvio.

Pluvio’s head chef, Warren Barr, grew up in destination restaurant kitchens. Like Fäviken, the cuisine at Pluvio drew on local and little known ingredients that changed with the seasons. Locally foraged mushrooms and sea asparagus complimented the halibut that was caught in local waters just hours before I ate it. Tasting a great northern bean at Pluvio was a mixed experience. On the one hand, it was so good I needed to close my eyes. On the other, it was sad to know just how much nuance and flavor the industrial food process has drained out of a can of beans.

An even bigger gap exists between the beef on offer at Pluvio and what goes into a typical hamburger. Beef at Pluvi comes from Fraser Valley, British Columbia farm that raises 100% Wagyu cattle, a rarity outside Japan. Wagyu is synonymous with quality because of the marbled and tender meat these animals produce. (I’ve never had it so can’t speak to the flavor).

Wagyu cattle don’t sleep in their own shit. On that Fraser Valley farm, cattle are raised with no added hormones or steroids. The diet of Wagyu cattle needs to be high quality to achieve the desired marbling of the meat. In Japan, the traditional Wagyu diet, "sukiyaki," includes a mix of soybeans, corn, wheat, and sake.5 Beer is sometimes added to the diet to improve digestive health, and many farmers traditionally rubbed the cows belly to aid the digestive process. Unlike the cow that was slaughtered at 12-15 months to make the burger, Wagyu cattle are slaughtered at 28-36 months.6

I will never understand what it’s like to be a cow. But I do believe, and am convinced that science will eventually confirm, that animals have more intense internal lives, complete with a broad spectrum of emotions, than we acknowledge today. (If you don’t believe me, I suggest picking up Ed Yong’s recent and magisterial An Immense World, which I recently wrote about.) No animal wants to spend its life immobilized, on a diet it can’t naturally digest, and left to sleep in its own filth.

Today scientists are openly talking about plant “intelligence”. The capacity of animals–and perhaps plants–to learn, grow, and understand the world exists. We just can’t tap into it because of limitations that come with approaching the world with a human-centered perspective.

We sat at the Pluvio bar, which allowed us to watch the chefs work in the open kitchen. Their pace was fast, but controlled and in flow. All three prepared several dishes at once, working from an internal clock that told them when to flip, turn, or plate a meal. There was no yelling; each referred to the others as chef, with the shift lead offering gentle guidance on how to properly garnish and present a plate.

Our meal unfurled slowly. This pacing gave us the space to move past our usual topics–logistics, childcare, work challenges–and towards our shared dreams and aspirations. It’s so easy to get caught up in the day-to-day that we end up somnambulating to an unwanted and unexpected destination. Slow food can give us the time to pause, survey the surroundings, and chart a new course.

Bringing Slow Food Home

One exceptional meal every few years will not set you free from the Shitthropocene. But you can establish more fulfilling relationships with food and those around one meal at a time.

Start with a commitment to screen-free meals. Sit and engage with the other members of your household. Across cultures and times, shared meals are how we establish and strengthen connections. It’s why so many cultural traditions include a festive meal. Each week, my family marks the start of Shabbat on Friday evening with the lighting of the candles, a few prayers, and a family meal.

This year, I volunteered to prepare the Passover Seder for my immediate family and in-laws. The seder is the one time all year I buy and prepare beef. Over the course of three days, I prepared the brisket and marked up the sections of the Haggadah I wanted to cover during the meal. Each hour of preparation translated into just a few minutes of the meal; a typical outcome when half your participants are under ten. Rushed or not, what mattered was the care I put into preparing a meal for those I love and sharing the Seder, with all of the ancient and familial traditions, with my kids. One day, we’ll go deep on the story and discuss the injustices in the world and what we can do to fight against them; for now, I’ll enjoy my two-year old dancing so hard to Dayenu that she fell over.

Holiday or not, I express love through cooking. Each week, I prepare a dinner menu. Over the years of doing this, I’ve determined that the right number of cookbooks to own is the number you have today plus one, and that shopping seasonally and with intention is a great way to expand your repertoire and connect your family to the world beyond. While my kids are fickle beasts, rejecting dishes that were recently their favorites, and often subsisting on plain noodles, yogurt, and fruit, I’ve come to understand that what they see on the table–and how we eat together as a family–matters.

As a young adult I lived and traveled across many parts of the world–Australia, China, Europe, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Levant. This exposed me to foods I’d never seen in Ohio in the 90s. Curries, dahls, olives, ducks, and dumplings–there was so much to explore. The more I ate, the better my understanding of that place and culture became.

When I returned to these cuisines as an adult in the kitchen, I appreciated them more. You can travel the world in your kitchen. All you need are cookbooks, directions to a few ethnic grocery stores, and patience. Slowly learning how to make a serviceable pad thai at home was a delight–having my kids decide that my pad thai stinks is part of life. Exploring ayurvedic staples like kitchari has connected me with my wife and given us a hearty go-to meal when the kids demand mac and cheese.

You can also explore the seasons of the year from your kitchen with the aid of cookbooks like Joshua McFadden’s Six Seasons. I’ll never be as connected to the land as the chefs and foragers that make a place like Pluvio so exceptional, but global and seasonal cooking push back on the homogenized blah of Shitthropocene food.

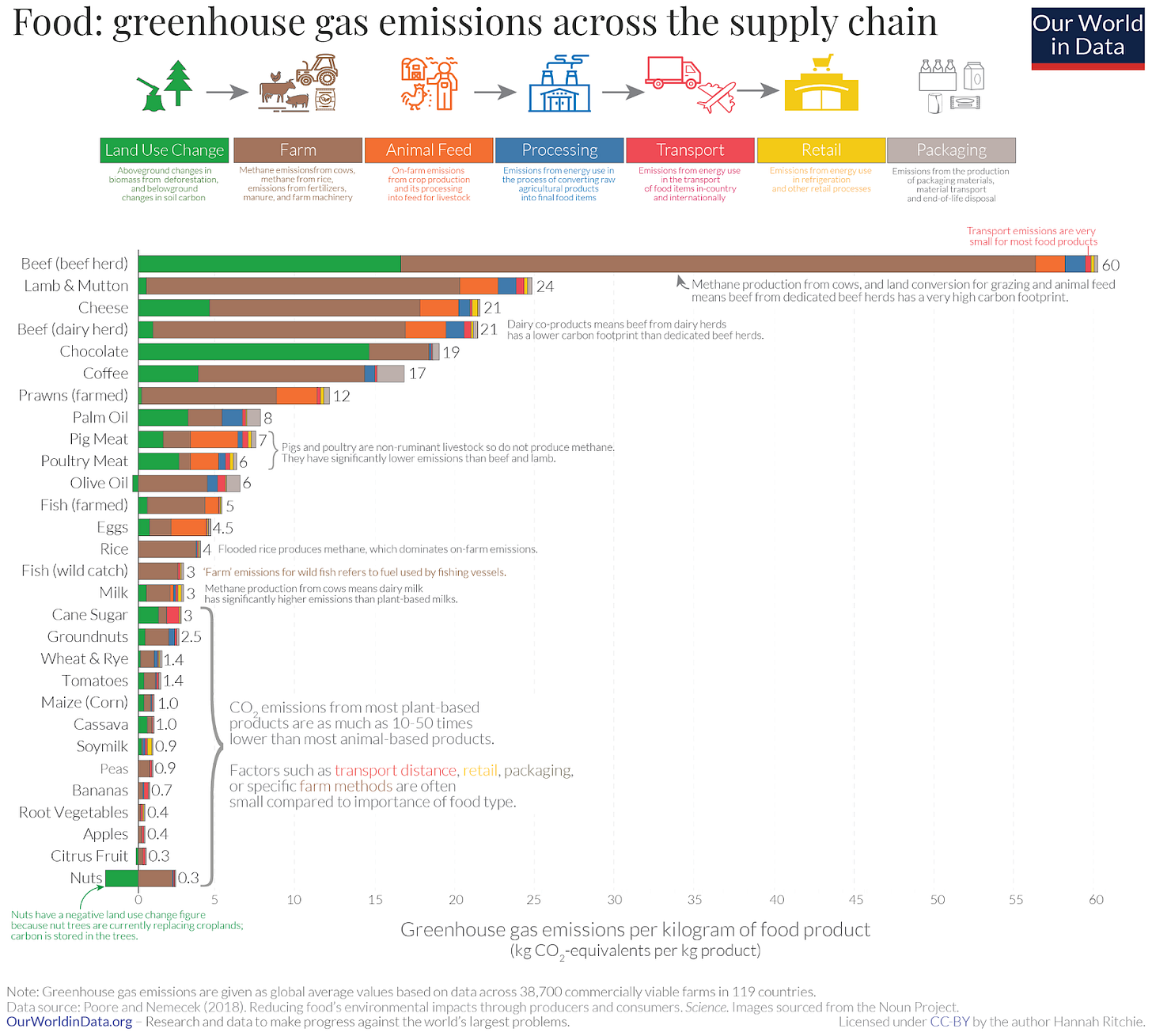

Eating healthy food, together with our families and removed from our screens, is better for us and the planet. Obesity and loneliness are both exacerbated by eating processed foods in front of screens. The environmental impact of the industrial food system, and especially meat, is massive. More than thirty-five percent of habitable land is used for livestock, with most of it going to graze cattle before they are sent to the CAFO. This land isn’t conjured from thin air; much of it used to be forests or grasslands. Similarly, a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions come from food production, with the largest impact per kg of food product is beef–and it isn’t even close.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local 7

The conclusion to draw from this graphic isn’t that you should never eat a burger. Rather, it’s that purchasing a burger has a massive environmental impact relative to other choices–and is implicitly supporting the industrialized meat production system I described above. Perhaps next time you go down the meat aisle, consider an Impossible Burger, or if you select beef, make it grass-fed.

Conclusion

The industrial food system, which is able to extract a tremendous number of calories from the land cheaply, is a modern miracle, but it comes with real costs to our physical and physiological health, and brought us into the shitthropocene of food.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The goals of the food system today will not be the goals of tomorrow if we demand that they change. If we demanded healthier, whole foods–if we asked that the Farm Bill be restructured to optimize for the health of people and the land instead of producing corn meant for gas tanks and CAFOs–if we refused to split our attention between people and screens during meals, things will change.

If we want to escape the Shitthropocene, there’s no better or more impactful place to start than in the kitchen.

Interviews - Michael Pollan | Modern Meat | FRONTLINE | PBS. (2015, November 18). https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/meat/interviews/pollan.html Accessed May 26, 2024.

Koerner, B. I. (2010, May 24). Making Cheetos: It ain’t easy being cheesy. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/2010/05/process-cheetos/ Accessed May 26, 2024.

La Marra, M., Caviglia, G., & Perrella, R. (2020). Using smartphones when eating Increases caloric intake in young people: An overview of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587886 Accessed May 26, 2024.

Slow Food Annual Report 2022. (n.d.). https://pub.slowfood.com/annual_report_2023/ Accessed May 20, 2024.

Hoffman, E. (2023, July 7). “What are wagyu cows fed? An insider’s guide.” WagyuWeTrust. https://wagyuwetrust.com/blogs/news/what-are-wagyu-cows-fed-an-insiders-guide Accessed May 24, 2024.

Hoffman, E. (2023, August 25). What is the lifespan of a Wagyu cow? WagyuWeTrust. https://wagyuwetrust.com/blogs/news/what-is-the-lifespan-of-a-wagyu-cow Accessed May 24, 2024.\

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2024, March 18). You want to reduce the carbon footprint of your food? Focus on what you eat, not whether your food is local. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/food-choice-vs-eating-local

This is your best posting yet. Mazes tov and thank you. But how do you pronounce “shitto…..?”