Change Happens at the Margins

A story about farmland in Iowa got me thinking about how to create a better future.

Every year, I take time to reflect during the Jewish High Holy Days. This year, I’ve been thinking about how lucky we are to live in a dynamic world. Multiple futures are possible, and as humans we can actively shape which one becomes reality. Of course the future could be worse—but it could also be better. So much rides on our actions.

This set up could go so many ways—it’s been a particularly long and challenging year—but I’m going to go deep on Prairie Strips Iowa. I’m not a farmer—hell, I’m not even a gardener—but these areas demonstrate the amazing resilience of our planet. Plants and animals are ready to return to their native lands if we give them an opening.

This is also true of new ideas and approaches to living. There are so many potential futures available if we’d only get out of our own collective way.

Prairie Strips

Before the settlers arrived, Iowa was 30 million acres of prairie land. Now less than 0.1% of that original prairie remains, with the majority replaced by a monoculture of corn and soybeans.

It seems bleak, but at the margins of these fields, in areas that are too degraded or steep for farming, the prairie is making a comeback through the Prairie Strips program. Though it is tiny—only 23,000 acres of Prairie Strips exist across seven states—the results and trajectory are promising.

To qualify as a Prairie Strip, dozens of native plant species must be planted in an area that’s at least 30 feet wide and adjacent to active cropland. Prairie strips provide oases for native species and restore soils. According to the academic research in Iowa,

Replacing 10% of cropland with prairie strips increased biodiversity and ecosystem services with minimal impacts on crop production. Compared with catchments containing only crops, integrating prairie strips into cropland led to greater catchment-level insect taxa richness (2.6-fold), pollinator abundance (3.5-fold), native bird species richness (2.1-fold), and abundance of bird species of greatest conservation need (2.1-fold). Use of prairie strips also reduced total water runoff from catchments by 37%, resulting in retention of 20 times more soil and 4.3 times more phosphorus…Social survey results indicated demand among both farming and nonfarming populations for the environmental outcomes produced by prairie strips. If federal and state policies were aligned to promote prairie strips, the practice would be applicable to 3.9 million ha of cropland in Iowa alone.

Beyond restoring the ecosystem, Prairie Strips provide people with a place to decompress and reflect after a bad day or find joy through picking flowers or seeing a bird. Nature restores us.

While Prairie Strip coverage has increased from only 600 acres in 7 states back in 2019 to 23,000 acres across 14 states today, that’s still just a rounding error when considering the almost 900 Million acres of farmland in the US.

Unfortunately, the economics of Prairie Strips make rapid expansion hard to envision without systemic change.

The Government pays farmers $209 per acre of Prairie Strip based on their inclusion in the federal Conservation Reserve Program. That sounds good, but with the cost of converting lands and taxes figured in, Iowa State researchers estimate that farmers lose $64 per Prairie Strip acre. When compared to the $482 per acre of corn and $603 per acre of soybeans that farmers make, you’re left with an economic challenge.1

With family farms struggling, can we really expect farmers to lose $500-$650 per acre to replace anything other than the most marginal lands with Prairie Strips?

And that’s the rub. Even when there are tremendous benefits to everything—land, people, soils, birds, pollinators, etc.—it’s hard to see Prairie Strips getting to scale because they won’t make economic sense for farmers unless something changes.

Prairie Strips need to go from being the exception to becoming the rule. But how?

Reform, Revolution, or Both?

Let’s assume that the goal is a healthy, vibrant midwest in which native flora and fauna flourish, soils are replenished, nutrient runoff doesn’t lead to dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico, and both farmers and livestock live lives of dignity. For this to happen, we need concepts like Prairie Strips to thrive.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to delivering systemic change that can allow Prairie Strips, or any other new concept, to thrive: reform and revolution.

Reformers are institutionalists who want to nudge the current system towards a better outcome. They often think of themselves as pragmatists. In this instance, they might work to update federal and state policies to make the economics of Prairie Strips more favorable. This could happen through additional subsidies for Prairie Strips, or paying farmers for the ecosystem service benefits the result from Prairie Strips and improved land stewardship. In either case, the goal is to update the economic calculus to make Prairie Strips as economically attractive as planting corn or soy.

The revolutionary approach would be to smash the agro-industrial complex and revert Iowa back to land of small hold farmers separated by natural lands like Prairie Strips. These small farms may look something like the Polyface Farms that Michael Pollan profiled and made famous in The Omnivore’s Dilemma.

Unfortunately, reformers and revolutionaries rarely get along. Instead of seeing how each approach benefits from the other, they tend to let the tyranny of petty differences cloud their judgement. We’re left in a classic Prisoner’s Dilemma in which both groups defect instead of collaborating, leaving everyone worse off.

It doesn’t have to be this way. We need to focus on areas of convergence, which tend to occur at the margins. Almost everything interesting happens at the edges—of an ecosystem, academic discipline, job function, or neighborhood. Over time, the edges can show the middle a better approach, and thereby change the entire system for the better.

To show how this is possible, let’s bring our attention back to Prairie Strips. By expanding the time horizon, it’s possible to see how working within the system to reform it can lead to revolutionary outcomes—albeit more slowly and incrementally than many would like.

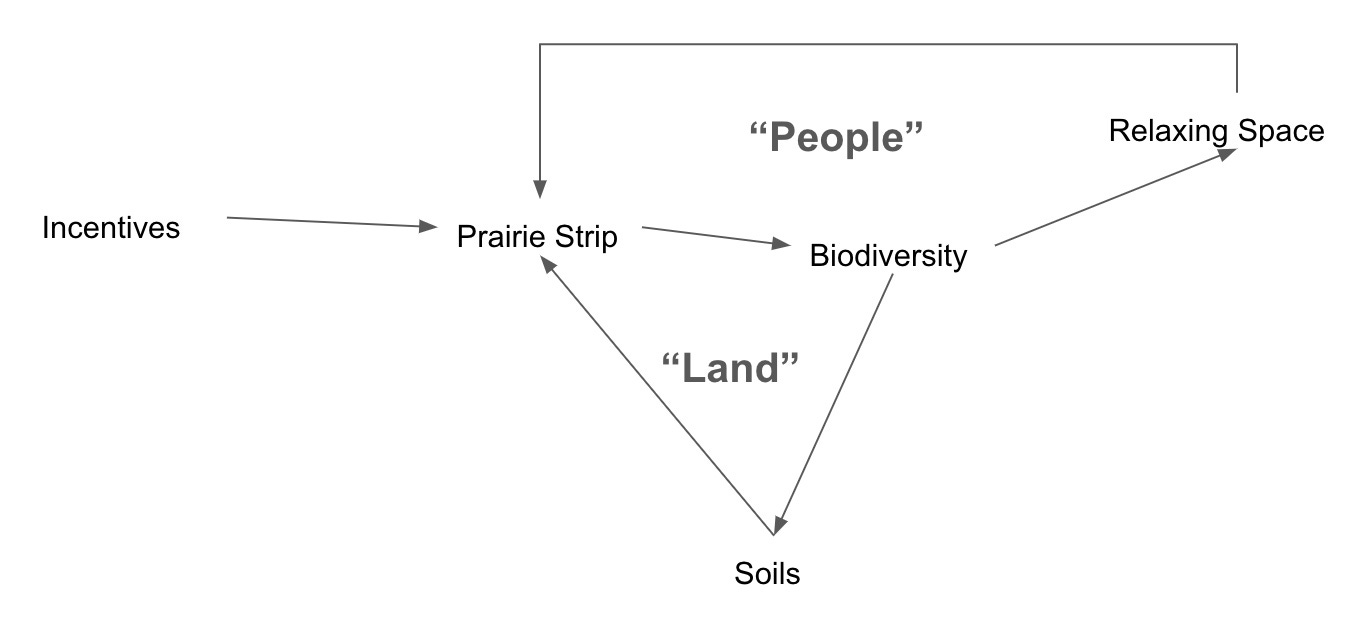

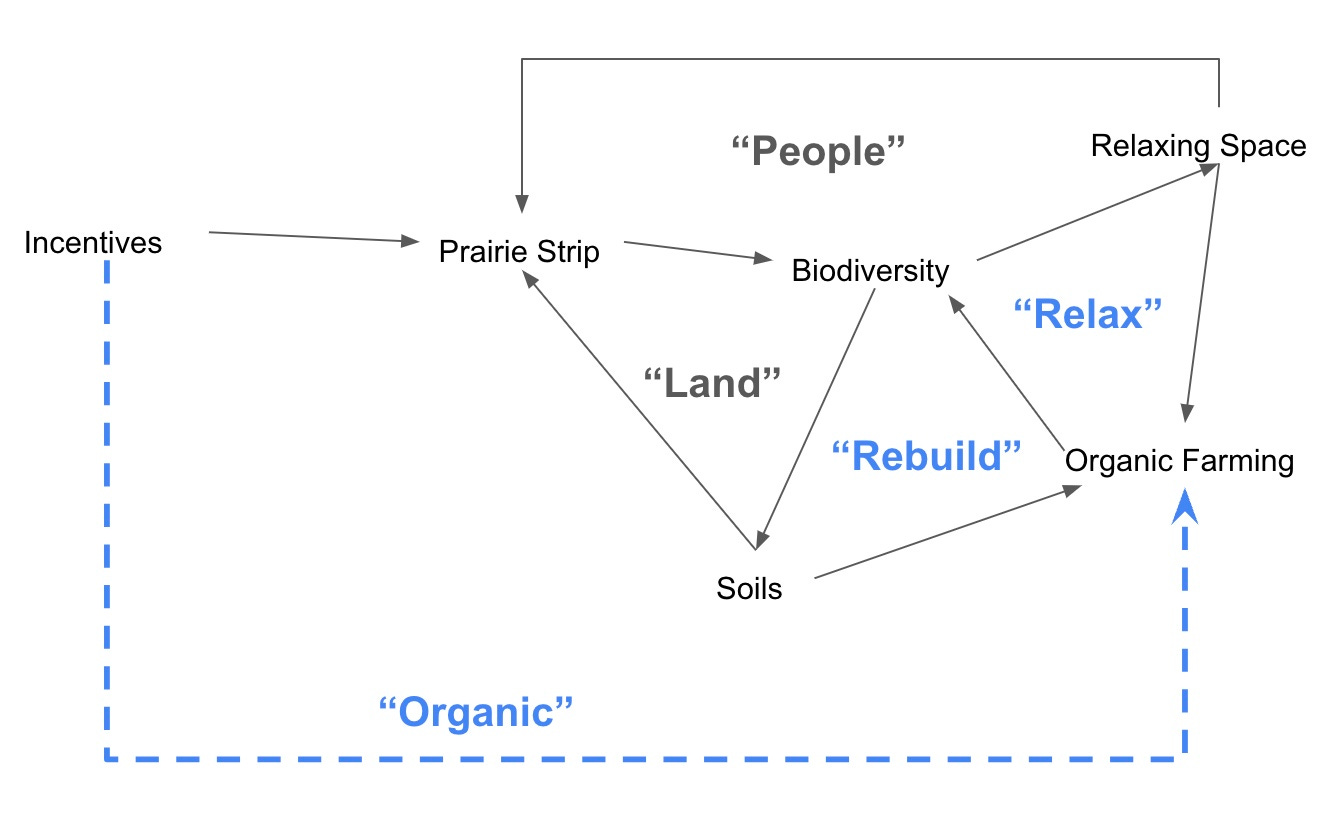

Reform

Let’s assume that we reform state and federal incentives so that Prairie Strips yield a better financial ROI than planting corn or soy. This should lead more farmers to convert edges of their properties and marginal lands to Prairie Strips. As the number of Prairie Strips increases, more native plants and animals will return to the land. This will do two things. First, it will improve the soils. As farmers see that the Prairie Strips benefit their land (or those of their neighbors) more farmers will invest in Prairie Strips, kicking off the “Land” feedback loop in which more Prairie Strips will lead to more biodiversity, which will improve the soils and lead to even more Prairie Strips. Second, the influx of biodiversity from Prairie Strips will create more relaxing spaces for farmers, their families, and their neighbors. As people come to enjoy the benefits of nature more immediately, they may be encouraged to plant additional Prairie Strips, which will activate the “People” feedback loop. With these flywheels spinning, it’s possible to imagine a future in which getting the Prairie Strip incentives right can move more of the 3.9 million acres of potential Prairie Strips from monoculture to biodiversity.

This is all great, but it doesn’t change the underlying fact that 69% of Iowa is covered by a monoculture of corn and soybeans.

Revolution

The reforms detailed above may be just the start. I believe that the improvement in soils and access to additional relaxing and natural spaces will encourage more people to seriously consider converting their lands to more organic, multi-crop farms à la the Polyface Farms. An increase in organic farms will kick off two additional flywheels: “Relax” and “Rebuild”. As the number of organic farms increases, the overall biodiversity of the area will increase, which will create additional places for people to relax and enjoy nature. The stark comparison between these areas and those dominated by industrial farming may encourage more people to convert to adopt a more biodiverse approach to farming. At the same time, the soil benefits of organic farming can rebuild interest in adopting more traditional approaches that are less reliant on using prodigious amounts of fertilizer.

As governments see the positive impact of this transition, they are likely to provide additional incentives that make the economics of organic farming more attractive than those of the monoculture, thereby activating the “Organic” feedback loop.

While this is obviously a highly simplified model and vision of the future, it shows that systemic change is possible, and that it can start with simple improvements.

Conclusion

As humans, we create systems and structures that constrain our behavior, and can often lead to unintended and harmful impacts to other animals and the planet. Yet it is a mistake to think that these systems can’t change, because nothing in our universe is static.

Farmland in the midwest is just one example, but it's illustrative of the larger truth that the most interesting opportunities are found on the edges. Our job is to find the leverage points on these edges and nudge them in a positive direction. Both reformers and revolutionaries have a role to play. My preference is to find areas on the edges that both groups can agree to, and start there. But that’s not always possible, so it’s important to be flexible. While any single action may seem small, in a dynamic world, it’s hard to forecast the impact that an action single action may have on our collective future.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/03/climate/iowa-prairie-farming-environment.html