His Name is Ayání Ashkíí

And he is creating a better future, one powwow dance and Native youth class at a time.

His name is Ayání Ashkíí, or Buffalo Boy—a name that reflects his early love of playing in the snow naked. He was born off the grid in the Bears Ears region of what is now Utah, where Native people have lived since time immemorial. When his family brought him into the hospital to get a birth certificate, the Government did not accept his name, so his uncle gave him the same English name as the President: Ronald.

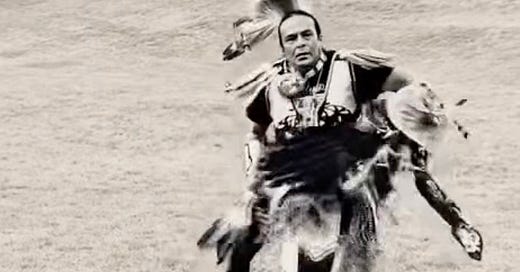

Navajo is his first language; beyond driving the shuttle that took me from a corporate retreat in Park City to the airport, he is a tattoo artist, traditional knowledge keeper, and exceptional powwow dancer. As we drove, he pulled up a short clip of him dancing and shared a picture of himself with a sculpture made in his image. He introduces himself as Tonka—tatanka is the Lakota word for Bison—and his Instagram handle is Tat_Tonka.

He is Northern Diné (Navajo) and a member of the bitterwater clan on his mother’s side; Hopi First Mesa and a member of the bear clan on his father’s side. Tonka was primarily raised by his Grandma because of the toll alcoholism took on his family. He teaches powwow dancing to Native youths and performs throughout the country.

He was raised in the Bears Ears area a few valleys away from his traditional homeland. In the 1860s, the US Army conducted a series of raids and a scorched-earth campaign that precipitated the Long Walk, or forced relocation of most of the Diné from their lands to the Bosque Redondo Reservation/internment camp hundreds of miles away. Tonka’s family wasn’t part of the Long Walk; when they saw the soldiers coming, they fled across the land bridges, or arches, and into a landscape where the horse-bound cavalry were unable to give chase.

Bears Ears was protected as a 1.35 million acre National Monument at the end of the Obama Presidency. The area boasts more than 100,000 cultural and archaeological sites (Enote), and has been managed cooperatively by the five local Tribes (the Hopi Tribe, Navajo Nation, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, and the Pueblo of Zuni), the Bureau of Land Management, and the Forest Service since 2022. Indigenous cultural artifacts mean little to President Trump, who has tried to shrink the Monument and open it to resource extraction each time he’s been President, and I fear for the future of the site. Tonka told me about the mining equipment that was starting to appear in the area, and mentioned a potential uranium mine.

He is at home in nature, and has guided 15 day survival courses for wilderness-curious but marginally skilled people like me. I asked what he brought on his trips into the wild.

“Nothing.”

“Not even a knife?”

“No, I make those out of flint. The rocks and landscape provide everything I need to survive.”

This left me agape, so I asked more about his connection to the land. He responded with an abridged version of the Diné creation story. Diné means people of the earth. According to their tradition, we are living in the Fourth World, and it will be destroyed like the first three if humans do not live the proper way. What follows is a simplified retelling of the story.

The First World, located far below where we are today, was dark and only included six Beings: First Man, First Woman, Salt Woman, Fire God, Coyote, and Begochiddy, a blue eyed, golden haired man-and-woman from a seashell. After Begochiddy created mountains, insects, ants and a few plants, the world was set aflame by the jealous Fire God, so Begochiddy created a Big Reed that led everyone to the Second World.

This World was blue and contained clouds and mountains, more plants, and more people, including the Swallow People and the Cat People. Everyone lived in harmony for a time, but eventually fighting broke out, so Begochiddy planted another Big Reed that led to the Third World.

The Third World was yellow and spectacular, but still lacked the moon and stars. It was in this World that Begochiddy created rivers and springs, birds and trees, lightning and water animals, and myriad humans who spoke the same language and lived in harmony. The harmonious society didn’t last; red streaks placed by First Man across the sky represented the diseases that were about to come. Men blamed women; women blamed men, and Begochiddy separated them on opposite sides of a river. After a time, the men and women asked to be reunited, which Begochiddy did, but he warned that the Third World would be destroyed by a flood if there was more trouble. In Tonka’s brief retelling to me in the shuttle, human vices like rape and murder reappeared, and so a flood came, with people eventually emerging into our world, the Fourth World, which was even more beautiful and glittering, but broken. (The versions I found online included additional details around Coyote kidnapping the baby of the Water Monster, who responded by flooding the Third World).

Tonka believes that our job in the Fourth World—this most beautiful and magnificent one, the glittering one, the only one with the Sun and Moon and Stars—is to live in harmony with the creatures and care for the land. As he explained it to me, every plant or animal he interacts with is trying to tell him something. It’s his responsibility to listen and understand what the creature is trying to tell him, for not every creature has the lips to speak or the eyes to see like we do.

Tonka’s wife, Rhonda "Honey" DuVall, is an expert in traditional herbs, medicines, and songs. Like Tonka, she is Diné, Tangle clan with African-American ancestors; her grandfather is Coyote Pass clan. Born and raised on the Diné reservation in Blue Gap, Arizona she is an R&B singer, storyteller, dancer, and songwriter as well as a Community and Cultural Specialist at the Urban Indian Center in Salt Lake City. She performs widely, teaching her audiences about Native American traditions. "I always dance for people other than myself because I know that we as indigenous people—or even non-indigenous—we all need the healing." (Utah Cultural Celebrations Center)

Providing that healing is central to who Honey and Tonka are. Driven to reconnect Native youths with the cultural traditions that were stripped from them in places like the Bosque Redondo Reservation or the Indian Boarding Schools, Honey founded Natives Aiming To Succeed Education Resource Center (NASERC), which “promotes a wide range of cultural opportunities, experiences, culture-based educational programs and leadership development for individuals of the AI/AN descent.” (You can donate here).

They offer dance and song classes, opportunities to perform, traditional medicine lessons, and excursions to the field to collect the plants needed to make these medicines. The classes have had a transformational effect; six of the kids who dance with him were students of the month at their schools and are set to graduate from high school. Intergenerational family bonds have been strengthened. Connecting to their roots has made these youths and families proud of who they are.

Learning from elders and lived experience is central to Tonka’s way of life. “My people believe that those who need to turn to books to seek knowledge are lost, because they have forgotten how to listen to the land and understand what it’s telling them. They have forgotten how to respect and follow the teachings of the Creator. We need to live in harmony with the rest of creation, my Brother.”

This epistemological system is far from my own. I was raised on the power of books, logic, and analytical thinking. Experiences are valuable, but generally within the context of human societies and institutions. I wasn’t trained to listen to natural systems, but rather to rely on quantifiable scientific measurements of things like glacial melt and parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This is useful information that can be transformed into knowledge, but it’s hard to derive wisdom from facts and figures. Wisdom is deeper.

The Diné have much to teach as an ancient and sophisticated culture. To be able to go into the mountains with nothing and thrive is something that no book can teach. To live and flourish within a landscape for thousands of years is beyond the capabilities of our industrialized society.

As we pulled up to the airport, Tonka invited me to come back to the area to join a dance class, take a field trip into the mountains to pick medicinal plants with the Native youths, and go to the sweat lodge. I plan to take him up on the offer; in return, I offered to help him and his wife if they find themselves in Seattle. Sometime next year, I plan to take a trip down to Bears Ears to spend time with him. Until then, I’m left with his request that I spread the word that we can—and must—live in harmony with the land and rest of creation.

As I sat at my gate, I wondered if our interaction was random or fated. Did it fit into the part of my brain rooted in facts, or the part that’s opening up to other forms of knowledge? There were only two plausible explanations–confirmation bias and synchronicity in the universe–and I found myself tilting towards the latter.

Confirmation bias is the scientific approach to explaining “coincidences” that keep occurring. It’s the idea that it’s easy to find instances that confirm our preexisting beliefs because we’re actively looking for them. For me, this most obviously manifests with this newsletter; since I started looking for people, groups, and movements that point towards a better future, I find them everywhere I go. A few years ago, I wouldn’t have engaged Tonka in a conversation about the land and his people—I would’ve ended the conversation with small talk about our dogs. But because I am searching for stories that indicate a better future is being built, I’m more curious and open when I meet people like Tonka.

The second option is universal synchronicity, or the belief that the universe is a mysterious but kind and knowing place that connects us to what we need. It’s a place that will respond to your latent desires if they are noble and you have an openness to accepting new possibilities wherever and whenever we find them, even—and often—in unexpected or inconvenient places and times. Carl Jung, the early 20th century Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist, defined synchronicity as “the coming together of inner and outer events in a way that cannot be explained by cause and effect and that is meaningful to the observer.” Meeting Tonka, who was a replacement for the person who was initially supposed to take me to the airport, seems too intentional to have been random.

So if forced to choose between scientific rationalism and a kind universe that inspires awe, I’ll take the latter. If nothing else, it’s a better way to go through this world—especially given how bleak the global outlook is right now.

Coming full circle, I believe that growth and learning from people like Tonka is the only way for us to rediscover our role as the keystone species we’ve always been. Not only is it the role the rest of the biosphere needs us to rediscover right now for their sake, but crucially, I have an intuition that such a rediscovery would also transform our souls and society for the better.