10 Things Humboldt Can Teach Us

Now mostly forgotten, Alexander Von Humboldt was the most famous scientist in the world 150 years ago. There's still a lot that he can teach us.

He was the most famous scientist in the world 150 years ago, yet almost no one in the English-speaking world knows his name today unless it's in reference to a penguin, university, park, or ocean current. The centennial celebration of his birth in 1869 was a global event. There were parties in Europe, Africa, Australia, and the Americas. More than 80,000 people celebrated in his hometown of Berlin; 8,000 packed the streets of Cleveland; and 25,0000 joined the festivities in New York.

Maybe it was the anti-German sentiment that flowed from World War I. Maybe it was that the culture moved on from his approach to science, which cut across disciplines and the divide between art and science with ease. Maybe his position as the headwater of our views on nature was so profound that it washed away the importance of his name. Regardless of why, Prussian-born Alexander Von Humboldt deserves more. I just finished Andrea Wulf’s magisterial account of his life and adventures, The Invention of Nature . (I’m currently reading his Personal Narratives travelogue of his adventures in South America from 1799-1804).

Here are 10 things that each of us can learn from Alexander von Humboldt.

Curiosity

Humboldt asked so many seemingly obvious questions that people mistook his curiosity for stupidity. Others were astonished that his pockets resembled those of a child, filled with scraps of paper, rocks, and plants. He didn’t care. He measured everything, including the blueness of the sky, and conducted experiments on himself, animals, and the world around him. He traveled to South America with instruments I’ve never of—chronometers, theodolites, quadrants, a dipping needle, a magnetometer, electrometers, eudiometers—and more well-known ones including telescopes, sextants, compasses, a pendulum, and barometers.

When he didn’t understand an observation or article, he’d ask the leading scholar in that field to explain it to him. Asking questions, observing closely, and always seeking to fit what he saw and learned into a broader context was his superpower.

Few are as curious as Humboldt, but a little childlike wonder could help us all.

Get Outside Your Niche

Though Humboldt wrote several dense, scientific tomes, most of his speaking and writing was geared towards a general audience. From 1827-1828 he delivered a series of lectures in Berlin that Wulf describes as

Lively, exhilarating, and utterly new. By not charging any entry fee, Humboldt democratized science: his packed audiences ranged from the royal family to coachmen, from students to servants, from scholars to bricklayers – and half of those attending were women.

Writing for a general audience expanded the reach of his ideas. Humboldt was the reason Darwin joined the crew of HMS Beagle. In a sense, Humboldt was with Darwin on his entire five-year journey; not only had Darwin committed Humboldt to memory, he kept all seven volumes of Humboldt’s Personal Narratives travelogue in his cramped quarters on the HMS Beagle. Darwin’s lively prose was a response to his reading of Humboldt.

Beyond Darwin, Humboldt influenced the American transcendentalists Emerson and Thoreau; George Marsh, who argue that nature wasn’t there to be “consumed” by humans, thereby sparking the 19th century conservation movement in the US; and John Muir, co-founder of the Sierra Club and father of Yosemite National Park. I could go on, but you get the idea.

When sitting down to write or speak, try to appeal to the widest audience possible. Eliminate jargon when possible.

If your work is accessible, you never know where it might lead, or who it might influence.

Be Persistent but Flexible

After several failed attempts to join an overseas expedition, Humboldt was eventually granted a rare passport to the Spanish colonies in America, where he traveled extensively from 1799-1804. After returning to Europe and settling in Paris, he spent decades publishing what he’d learned. His more than 30 books ranged from Personal Narratives to a series of excruciatingly detailed scientific reports cataloguing the plants he’d collected. The persistence to write and publish so much – often in beautiful folios that he paid to print, thereby ruining himself financially – is inspiring. But one adventure wasn’t enough for Humboldt.

Almost as soon as he returned to Europe, he was ready to explore more. In particular, he wanted to go to India to see the Himalayas and compare them to the peaks of the Andes, especially Chimborazo. He first petitioned the British East India Company to let him travel to India in 1814 and was rejected. He returned to London to ask again in 1817. He kept asking. He was never able to get permission to visit India, but in a lucky break the Tsar eventually granted him permission to travel through Russia, ostensibly to leverage his training as a geologist to inspect Russian mines and help them discover precious minerals (which he did), though mostly to see the Altai mountains in Central Asia. He left for Russia in 1829, after 15 years of trying (and ultimately failing) to see the Himalayas. He was 59.

His trip to Russia wouldn’t disappoint.

Courage

Humboldt embodied both physical and moral courage. He traveled through dense Amazonian jungles and the Central Asian steppe, braving jaguars, crocodiles, spiders, and ferocious mosquitos. He summited mountains—his trek up Chimborazo held the world record for the highest ascent for decades—and could walk for days without tiring. Even during his trip to Russia, his physical stamina amazed his companions.

More important was his moral courage. He rightly saw and wrote about:

The evils of slavery;

The ills of colonialism and its role in destroying indigenous communities and the environment; and

The equality of human capabilities and potential regardless of race or culture at a time when many Europeans thought that they were objectively superior to people from Africa and the Americas.

Open-Mindedness

He was open to going where the facts and his observations took him. The knowledge of the indigenous peoples he met in the Amazon astonished him—he viewed them as the keenest observers of nature he’d ever met. They could distinguish plants and animals in a way that far exceeded his capabilities. He was also amazed by the complexity of the Aztec art and language.

From a scientific perspective, he was the first to realize that the magnetic equator was not in the same location as the physical equator and an early believer in the theory that volcanos are connected underground. His observation that animals are subject to the forces of competition influenced many, including Charles Darwin.

Microscope to Telescope

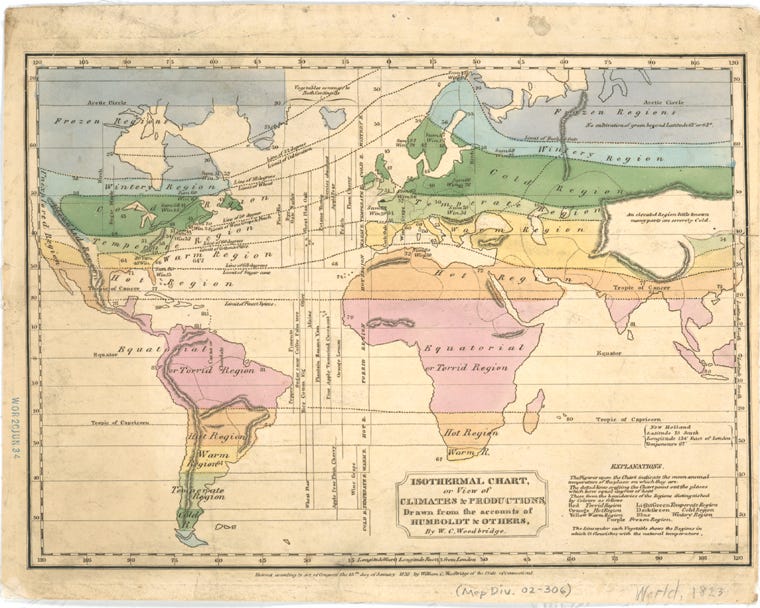

Ralph Waldo Emerson described Humboldt as one “whose eyes are natural microscopes & telescopes.” Humboldt could effortlessly move from the tiniest detail of a plant to the macro-view of an ecosystem. He was the first to recognize that plants and animals in different parts of the world responded to the same natural pressures—altitude, weather, geography—in similar ways. This was a radical insight that is beautifully depicted in his Naturgemalde, which shows how altitude, temperature, and humidity create unique zones of vegetation on Chimborazo.

Not only were the plants in South America influenced by their climate; Humboldt could also see the parallels to plants in Europe. He was the first to define global climate zones, or isotherms (today we most often see these on weather maps).

Connections, Context, and Patterns

This may be implicit in much of what I’m writing, but it’s so important that I’m going to call it out. Humboldt didn’t revel in the details for their own sake. He wrote:

Rather than discovering new, isolated facts I preferred linking already known ones together. The discovery of a new genus seemed to me far less interesting than an observation on the geographical relations of plants, or the migration of social plants, and the heights that different plants reach on the peaks of the cordilleras.

Humboldt was obsessed with synthesis, or as he put it, la physique générale. He needed to understand how all components of our natural world influenced, mimicked, and were connected to each other. He devoted his life to building up an encyclopedic knowledge of how each part of nature behaved and interacted with others.

He wasn’t multi-disciplinary so much as he preceded the division of science into discrete fields like geology and biology that occurred in the German university system (and spread to the US after it was adopted by Johns Hopkins University).

In our current society, with its glorification of deep expertise and an abundance of impenetrable and exclusionary jargon, we could all benefit from exiting our trenches of expertise for a moment to look around and talk to people in neighboring or distant areas of expertise. The best insights can come when we stop looking down and start looking around. Don’t believe me? Read Range, a great book on the benefits of being a generalist.

Art & Science

Humboldt rejected the division of art and science. In his youth, Humboldt spent considerable time with Johann Wolfgang Goethe, the great German author and scientist. They geeked out on rocks, fossil, plants, and the latest scientific discoveries. Goethe was such a fan of Humboldt’s work that he described spending a few days with Humboldt like “having lived several years.” Humboldt felt similarly and dedicated Essays on the Geography of Plants to Goethe, who devoured everything Humboldt wrote.

They were friends because Goethe was both a literary giant and a scientist; Humboldt was a scientist who loved the arts. He infused his writing with his passion for how nature made him feel.

When we separate facts and our emotional response to those facts, we lose part of what makes us human. Readers return to dry writing like they return to a dry, over-baked piece of chicken—only when forced to. If you see opportunities to break the boundary between art and science, do it. The more authentic you are in describing how something moves you, the more likely people are to respond to you.

Gracious Mentor and Correspondent

Humboldt was a gracious and intentional mentor. He believed that, “without a diversity of opinion, the discovery of truth is impossible.” In September 1828, he invited the leading European scientists to Berlin. As Wulf wrote,

Unlike previous meetings at which scientists had endlessly presented papers about their own work, Humboldt put together a very different programme. Rather than being talked at, he wanted scientists to talk with each other. There were convivial meals and social outings…Humboldt encouraged scientists to gather in small groups and across disciplines. He connected the visiting scientists on a more personal level, ensuring that they forged friendships that would foster close networks. He envisages an interdisciplinary brotherhood of scientist who would exchange and share knowledge.

Beyond bringing scientists together, he mentored and helped finance the excursions and research of numerous early career scientists.

If you wrote to Humboldt, he’s respond—personally. Near the end of his life, he received up to 5,000 letters a year and responded to most of them. When people knocked on his door to meet him, he always had time to speak with them (he had a soft spot for Americans). While it is true that he rarely let anyone else get a word in, had a biting wit, and a sometimes-vicious tongue, his willingness to engage with those who reached out to him is a model to emulate.

When I was much younger, I wrote a letter to a retired policy official. I expected nothing, but his office got in touch and scheduled an in-person meeting. The thirty minutes he spent with me had an outside impact on my career trajectory.

Look for ways that you can pass it on in your own way.

Adventure at Any Age

Humboldt left Prussia for Russia when he was 59. His was under direct orders from the Tsar to inspect mines and not travel further west than Tobolsk. At every stop on the 2,000 mile journey to Tobolsk he was greeted by Russian officials. He was being watched, and he knew it.

Instead of turning around in Tobolsk like he was supposed to, he decided to head further east to the Altai mountains, eventually reaching the Russian border with Mongolia and China. He crossed the river and left Russia to briefly meet with government officials from China, and then Mongolia. He was happy. Having already abandoned his itinerary long ago, he made another detour through the Kazakh Steppe where ethnic Kyrgyz lived and then to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea before returning to Moscow.

When you have the chance to go on an adventure, do it. If you have the option to go off the beaten path, take it – you won’t regret it.

Great and interesting read as always!